NAME John Eliot

WHAT FAMOUS FOR John Eliot is renowned as the "Apostle to the Indians," a Puritan missionary who dedicated his life to evangelizing Native Americans in New England. He is also famous for translating the Bible into the Algonquian language, the first Bible printed in North America

BIRTH Baptized on August 5, 1604, in Widford, Hertfordshire, England.

FAMILY BACKGROUND He was the son of Bennett Eliot and Letteye Aggar. His father was described as a yeoman, indicating he was a landowner of some means, farming his own land in Hertfordshire. The family appears to have been reasonably prosperous and adhered to Puritan beliefs. John had several siblings.

CHILDHOOD Eliot grew up in Nazeing, Essex, where he expressed gratitude for being raised with prayer and exposure to the Word of God. He likely attended a village school before pursuing higher education. His upbringing would have included religious instruction and the values associated with Puritanism. (1)

EDUCATION Eliot attended Jesus College, Cambridge, a notable centre for Puritan thought at the time.

CAREER RECORD After Cambridge, he worked as an assistant teacher at a grammar school in Little Baddow, Essex, under the guidance of the prominent Puritan minister Thomas Hooker.

Due to his nonconformist Puritan beliefs and the increasing pressure from Archbishop Laud in England, Eliot emigrated to the Massachusetts Bay Colony, arriving in Boston on November 3, 1631.

He served as pastor of Roxbury Church for over 60 years

Beginning around 1646, Eliot dedicated himself to evangelizing the local Algonquian-speaking Native Americans.

From 1651 onwards, Eliot established planned settlements for Native American converts ("Praying Indians"). Natick, Massachusetts, was the first and most famous.

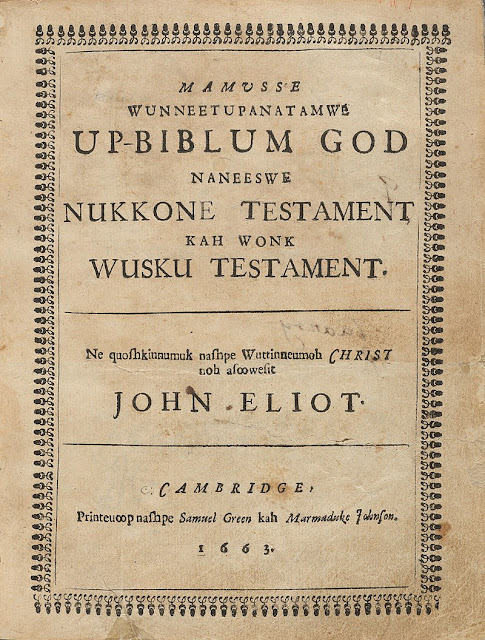

His most enduring work was the translation of the Bible. The New Testament appeared in 1661, and the complete Bible (Mamusses Wunneetupanatamwe Up-Biblum God) was published in 1663.

APPEARANCE No reliable contemporary portraits of John Eliot are known to exist. Several 19th-century engraved portraits of John Eliot exist, often based on earlier 17th-century paintings. As a 17th-century Puritan minister, he would likely have presented a sober and modest appearance.

|

| John Eliot |

FASHION He would have worn the typical attire of a Puritan clergyman of his time: plain, dark, functional clothing, likely including a Geneva gown for preaching, avoiding ostentation in line with Puritan values.

CHARACTER Contemporary accounts and his actions depict Eliot as deeply pious, zealous, incredibly persistent, patient, and compassionate (especially towards the Native Americans he sought to convert). He was known for his linguistic ability, dedication, and tireless work ethic.

SPEAKING VOICE In 1646, John Eliot began preaching to the local Native Americans at Nonantum, notably delivering his first sermon in their own Algonquian dialect using Ezekiel 37:9. This marked the first time they had heard the Christian Gospel preached in their native tongue.

Eliot's preaching style was described as simple yet profound by Cotton Mather, suitable for both learned audiences and "the lambs of the flock." (2)

SENSE OF HUMOUR Puritan writings rarely focused on personal humour. While he may have possessed a sense of humour, it is not a documented aspect of his personality.

RELATIONSHIPS John Eliot married Hanna Mumford in October 1632, shortly after she arrived in Massachusetts, in Roxbury's first wedding ceremony. The couple remained married for 55 years. They had six children (one daughter, Hanna, and five sons: John, Joseph, Samuel, Aaron, and Benjamin), several of whom also entered the ministry.

Eliot worked closely with other Puritan ministers like Thomas Hooker (briefly in England), Thomas Shepard, and Richard Mather.

Eliot's life's work revolved around his relationship with various Algonquian groups. This was complex, involving preaching, teaching, translation, establishing communities, and advocating for them, all within the framework of conversion and cultural change.

|

| Eliot among the the Indians from Mary Gay Humphreys book Missionary explorers among the American Indians |

MONEY AND FAME As a Puritan minister, Eliot lived modestly on a salary provided by his congregation and supplemented by funds from the "Corporation for the Propagation of the Gospel in New England" (based in London) for his missionary work. He did not seek personal wealth. He achieved considerable fame both in New England and England for his missionary activities and especially for his Bible translation.

FOOD AND DRINK His diet would have consisted of the typical food and drink available in 17th-century New England – local game, fish, cultivated crops like corn and squash, bread, and likely beer or cider.

MUSIC AND ARTS Puritan worship focused heavily on psalm singing, often unaccompanied or simply lined out. Eliot translated the Psalms into Massachusett for use in worship.

Beyond functional religious music, there's no record of particular interest in secular music or the visual arts, which were often viewed with suspicion by stricter Puritans.

LITERATURE Eliot's primary focus was religious literature. His most significant literary contributions were his own translations and writings in the Massachusett language: the Bible, primers, catechisms, grammars, and translations of other devotional works like Richard Baxter's Call to the Unconverted. He also authored works in English, such as The Christian Commonwealth (1659) and various tracts and reports on his missionary progress.

|

| The Eliot Indian Bible, the first Bible printed in British North America |

NATURE Eliot lived and worked immersed in the natural environment of colonial Massachusetts, travelling through forests and interacting with the land. However, his writings view nature primarily through a theological lens – as God's creation and the setting for human and divine activity, rather than expressing appreciation for nature in a romantic or aesthetic sense.

HOBBIES AND SPORTS Puritan culture emphasized work, duty, and religious observance over leisure activities common today.

SCIENCE AND MATHS While his Cambridge education would have included the standard curriculum of the time, Eliot is not known for any specific contributions to or particular interest in science or mathematics beyond what was generally understood. His intellectual focus was overwhelmingly theological and linguistic.

MISSIONARY CAREER John Eliot was a man who didn’t exactly do things by halves. If most of us were inclined to start something life-changing at the age of forty, we might content ourselves with buying a new hat or finally fixing the leaky roof. Not Eliot. He decided to become the first major missionary to Native Americans in New England, which—needless to say—involved a great deal more than handing out leaflets and saying things like “Have you heard the good news?”

So there he was, balancing a perfectly respectable job as pastor of Roxbury Church while simultaneously diving into a language that had, up to that point, absolutely no desire to be written down, let alone grammatical. The Massachusett language was, as Eliot probably muttered to himself on more than one occasion, “not exactly Latin.” Undeterred, he joined forces with a young interpreter called Cockenoe (who must have had the patience of several saints) and together they cobbled together something resembling a system: a grammar, a dictionary, and a small hope that words might eventually line up and behave.

Now, translating the Bible into English is hard enough, but into an unwritten Algonquian language? That’s the sort of task you usually dream about halfway through a bad curry. Yet Eliot did it. First the New Testament in 1661, then the Old Testament in 1663, neatly making his edition the first complete Bible ever printed in North America. It was, as you might imagine, not a light read—but it was a monumental achievement, especially given that it was probably typeset with hands trembling from exhaustion and eyes permanently squinting at unfamiliar vowels.

Not content with simply handing over Bibles and calling it a day, Eliot then set about creating what became known as “praying towns.” Fourteen of them, in fact. These were communities where converted Native Americans—“praying Indians”—lived according to Christian principles, which unfortunately came packaged with European haircuts and wardrobes, and other cultural adjustments that might have felt, to put it mildly, rather bewildering. Natick, the flagship town, had proper streets and plots and everything. It was a sort of hopeful utopia, at least in Eliot’s mind.

Eliot didn’t just sit back and let the towns do the work. No, he hopped on his horse—or walked, if that noble beast wasn’t available—and preached through forests, marshes, and whatever else colonial Massachusetts could throw at him. He catechized children, taught adults both the art of prayer and the slightly less spiritual skill of salting fish, and he fielded all manner of theological questions from Native leaders. Some of these were extremely tricky, and one imagines him occasionally wishing he’d brought along someone like Thomas Aquinas—or at the very least a warm blanket.

And then, of course, came King Philip’s War. A miserable time all around, full of suspicion, chaos, and burned villages. Eliot’s praying towns were caught in the middle, distrusted by both sides. Many were destroyed, and Eliot—now well into his later years—found himself scrambling to salvage what remained. He didn’t give up, of course. One gets the feeling he wasn’t very good at giving up.

In the end, Eliot’s efforts laid a foundation—not just in the literal sense, with town plots and chapels, but for the entire idea of missionary work among indigenous peoples. His story helped inspire the formation of the first missionary society in England, with the rather direct title: The Company for Propagating the Gospel in New England. And for nearly two centuries after his death, people still pointed to Eliot as a model of missionary zeal—albeit one who, by all accounts, would have benefited from a few long naps and a decent pair of shoes.

PHILOSOPHY & THEOLOGY Eliot was a staunch Calvinist Puritan. His theology emphasized God's sovereignty, predestination, the authority of the Bible, the necessity of a personal conversion experience, and the importance of creating a godly society (a "City upon a Hill").

His missionary work stemmed from the belief that all people, including Native Americans, needed to hear the Gospel for salvation.

Eliot's book The Christian Commonwealth laid out a model for civil government based directly on the Bible, reflecting his theocratic ideals.

POLITICS Eliot operated within the political structure of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. His main political activity involved advocating for the Praying Indians, seeking land grants for their towns, and defending them, particularly during and after King Philip's War.

Eliot's publication of The Christian Commonwealth was a significant political act, proposing a scripturally-based alternative to traditional forms of government. It is considered the first book on politics written by an American, as well as the first book to be banned by a North American governmental unit.

SCANDAL The closest thing to a public scandal was the controversy surrounding his book The Christian Commonwealth.

MILITARY RECORD Eliot's life and work were profoundly affected by colonial conflicts, most notably King Philip's War (1675-1676), which led to the destruction of many Praying Towns and the persecution of his Native American converts.

HEALTH AND PHYSICAL FITNESS Eliot lived to be about 85 or 86 years old, an advanced age for the 17th century, suggesting generally robust health. His extensive travels on foot and horseback for his missionary work across eastern Massachusetts required considerable physical stamina.

HOMES Eliot spent part of his early life in the village of Little Baddow, Essex. After graduating from Jesus College, Cambridge, Eliot became an assistant schoolmaster in Little Baddow around 1629, where he taught at the grammar school and was influenced by Puritan teachings.

It was during his time in Little Baddow that Eliot came under the influence of Thomas Hooker, a prominent Puritan minister who would later emigrate to America himself. Hooker’s mentorship had a profound impact on Eliot’s theological development and likely helped ignite the spark that eventually led him to pursue missionary work in New England. (4)

|

| Cuckoos Farm, Little Baddow, Eliot's home around 1629 Wikipedia |

Upon emigrating, he settled in Roxbury, Massachusetts.

TRAVEL When Eliot emigrated to Boston, Massachusetts, he arranged passage as chaplain on the ship Lyon and arriving on November 3, 1631. (3)

Eliot regularly travelled throughout eastern Massachusetts and potentially into neighbouring areas (like parts of Connecticut) to preach and minister to different Native American communities. These journeys were often arduous, undertaken on foot or horseback through wilderness areas.

DEATH John Eliot died in Roxbury, Massachusetts, on May 21, 1690. He continued his ministry almost until the end.

Eliot was buried in the Eliot Burying Ground, also known as the Eustis Street Burying Ground, in Roxbury, Massachusetts. This cemetery is one of the oldest in Boston and contains the graves of many prominent early colonial figures. Eliot's resting place is located in the "Minister’s or Parish Tomb," which also holds the remains of five other ministers from the First Church of Roxbury

APPEARANCES IN MEDIA Eliot is primarily a figure in historical and theological literature. He features prominently in histories of Puritan New England, missionary work, Native American history of the colonial period, and the history of Bible translation.

Translated the Bible into Algonquian (first printed Bible in North America).

Established 14 praying towns for Christian Native Americans.

Authored several religious texts promoting Puritan ideals.

Oversaw education initiatives like Roxbury Grammar School

No comments:

Post a Comment